“How long will it take to produce this?”

“Well… who’s going to do it?”

“Who ‘s available? Paul would be great, but he takes longer…”

“Marie too, but someone would need to review it because…”

Does that sound familiar?

Scoping is risky: if you get it wrong, you may lose money, or piss off annoy your client when you’ll ask for more money and time to complete the job. Nobody wants that, right?

Worst: you may end up forcing people to produce something with not enough time to do it properly.

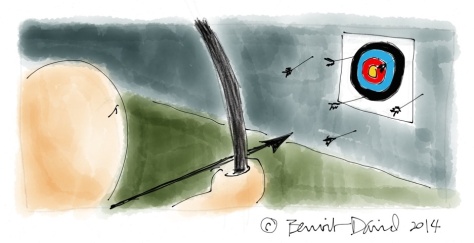

GOAL:

Get better at scoping to hit the target!

PLAN:

Capitalise on your experience to minimise guessing & minimise risk.

A little while ago I posted Training Projects: How much does it cost? How long will it take? and finished it by suggesting to keep track of the effort spent during your projects, in the same way you estimated it in the first place. This way you collect data on which you can base future estimates.

HOW?

Create your own ratios for tasks, roles or deliverables.

First you breakdown your project like a story: sequence what needs to be done and identify who will do it. You end up with your lists of deliverables and roles that need to be filled.

About the roles… Different roles dictate rates, especially when some roles require different levels of expertise. You may use the same person to fill different roles, but if it implies tapping into different levels of expertise, it will raise the question of different rates. You may want to charge one rate to lessen accounting, but this would raise the value your client is getting for the rate you’re charging… One could argue that “higher-paid” resources are faster at “lesser” tasks, but it is a [very] contentious question… Separate role-based rates make it easier to track data and create your own ratios, even if it requires more “accounting”.

So let’s look at an example, very simplified example of a completed tracking table, after a project…

| Task | Hrs (estimate) | Hrs (actual) | Role | $ |

| Analysis | (sum) | (sum) | … | |

| Review materials |

16

|

12 | Senior ID | … |

| Meetings and discussion |

8

|

10 | Senior ID |

…

|

| Write-up of Design Document |

40

|

36 | Senior ID |

…

|

| Etc. |

…

|

|||

| Storyboarding | (sum) | (sum) | … | |

| Module 1 | (sub-sum) | (sub-sum) | … | |

| Lead Support |

4

|

7 | Senior ID |

…

|

| Alpha |

24

|

28 | ID |

…

|

| QC Content |

8

|

4 | Copy Editor |

…

|

| Edits after client review |

4

|

8 | ID |

…

|

| Etc. |

…

|

|||

| Module 2 | (sub-sum) | (sub-sum) | … | |

| Lead Support |

6

|

3 | Senior ID |

…

|

| Etc. |

…

|

Tracking [more] detailed data allow you to determine your…

- Effort/cost per deliverable

- Effort/cost per role

- Effort/cost per unit of learning, like an hour of elearning

With this data you can compare the estimate to the actuals, figure out why there are differences, identify those that you can control, and take notes for the next scoping exercise. 🙂

The level of detail is up to you. For sure the temptation of diving into details is great. We have to be careful with that: too much detail becomes counter-productive. The key is to first define what you want to know, then identify the data you need.

For sure this requires more “accounting”. And to be viable, you likely need a timesheet system that supports it, more [PM] time to enter the estimated data AND discipline of ALL resources to enter the data properly.

Do you think it’s worth it? 🙂